CANNABIS :

OUR POSITION FOR A CANADIAN PUBLIC POLICY

REPORT OF THE SENATE SPECIAL COMMITTEE ON ILLEGAL DRUGS

SUMMARY

Chairman: Pierre Claude Nolin

Deputy Chairman: Colin Kenny

SEPTEMBER 2002

OUR POSITION FOR A CANADIAN PUBLIC POLICY

REPORT OF THE SENATE SPECIAL COMMITTEE ON ILLEGAL DRUGS

SUMMARY

Chairman: Pierre Claude Nolin

Deputy Chairman: Colin Kenny

SEPTEMBER 2002

While this is the Summary, I believe everyone should read it. You don't have to be a politician or a lawyer to understand:

Tolerance

Reduced response of an organism and increased capacity to support the effects of a substance after a more or less lengthy period of use. Tolerance levels are extremely variable between substances, and tolerance to cannabis is believed to be lower than for most other drugs, including tobacco and alcohol.

Characteristic of a substance which induces intoxication, i.e., “poisoning”. Many substances, including some common foods, have some level of toxicity. Cannabis presents almost no toxicity and cannot lead to an overdose.

Introduction

The Senate Special Committee on Illegal Drugs addressed the question of drugs just as everyone else does, with the same preconceptions, attitudes, fears and anxieties we all share. Of course, we had at our disposal the 1996 study our colleagues conducted on government legislation dealing with illegal drugs, which had enabled them to hear a number of witnesses over several months. We also knew at the outset that research expertise would be available to us, but it is still difficult to overcome attitudes and opinions that we have long taken for granted. Whether one is in favour of enhanced enforcement or, on the contrary, greater liberalization, opinions often resist the facts and in a field such as this the production of facts, even through scientific research, is not necessarily a neutral undertaking. We, like you, have our prejudices and preconceptions. Together we must make the effort to go beyond such predispositions. That is one of the objectives of this report.

The public policy regime we propose expresses the fundamental premise underlying our report: in a free and democratic society, which recognizes fundamentally but not exclusively the rule of law as the source of normative rules and in which government must promote autonomy as far as possible and therefore make only sparing use of the instruments of constraint, public policy on psychoactive substances must be structured around guiding principles respecting the life, health, security and rights and freedoms of individuals, who, naturally and legitimately, seek their own well-being and development and can recognize the presence, difference and equality of others.

We are aware, as much now as we were at the start of our work, that there is no pre-established consensus in Canadian society on public policy choices in the area of drugs. In fact, our research has shown us that there are few societies where there is a broadly shared consensus among the general public, let alone between the public and experts. We are well aware, perhaps more so than at the outset, that the question of illegal drugs, viewed from the standpoint of public policy, has a broad international context and that we cannot think or act in isolation. We know our proposals are provocative, that they will meet with resistance. However, we are also convinced that Canadian society has the maturity and openness to welcome an informed debate.

Further points throughout the Summary include:

Ø Cannabis itself is not a cause of other drug use. In this sense, we reject the gateway theory.

The relationship between cannabis use and delinquency and crime, based on research evidence, we concluded that:

Ø Cannabis itself is not a cause of delinquency and crime; and

Ø Cannabis is not a cause of violence.

Chapter 12 - The National Legislative Context

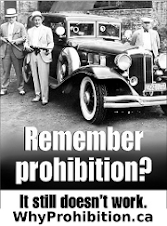

Drugs have been prohibited for fewer than a hundred years; cannabis for slightly more than 75 years. It is tempting to think that the decisions made over the years to use criminal law to fight the production and use of certain drugs are in keeping with social progress and the advancement of scientific knowledge about drugs. But is this really the case? The history of legislation governing illegal drugs in Canada, like the analysis in Chapter 19 of the structure of international conventions, suggests that it is highly doubtful. To what extent is such reasoning really rational? Is the rationale of the system of controls acceptable in the eyes of civil society, users as well as abstainers? What criteria motivated legislator decisions? Indeed, were there criteria? What motivated parliamentarians from Canada and elsewhere to prohibit certain substances, to control access to certain others, and to permit still others to be sold over the counter?

Knowing where we have been helps in understanding where we are going. That is the goal of this chapter, retracing the evolution of Canadian drug laws from 1908 to the present day. We have identified three legislative periods. The first, and longest, spans 1908 to 1960, the period of hysteria. We were told that drugs were made criminal because they are dangerous. Analysis of debates in Parliament and in media accounts clearly shows how far this is from truth. When cannabis was introduced in the legislation on narcotics in 1923, there was no debate, no justification, in fact many members did not even know what cannabis was.

The second period, much shorter, runs from 1961 to 1975, the search for lost reason. Following the explosion in drug use in the early 1960s and demands for reform from various sectors of society, governments appointed a commission of inquiry in Canada, the Le Dain Commission. Last comes the contemporary period at the beginning of the 1980s. Reform is not on the policy agenda any more and anti-drug policies have forged ahead.

In summary, we observed that:

Ø Early drug legislation was largely based on a moral panic, racist sentiment and a notorious absence of debate;

Ø Drug legislation often contained particularly severe provisions, such as reverse onus and cruel and unusual sentences; and

Ø The work of the Le Dain Commission laid the foundation for a more rational approach to illegal drug policy by attempting to rely on research data. The Le Dain Commission's work had no legislative outcome until 1996 in certain provisions of the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act, particularly with regard to cannabis.

http://www.parl.gc.ca/37/1/parlbus/commbus/senate/com-e/ille-e/rep-e/summary-e.htm

Knowing this it's quite astonishing the Conservatives and Liberals are pushing Mandatory Minimum Sentencing. All so they can trumpet "We're tough on crime!"

When people hear the word "crime", they are most probably thinking of murder, rape, armed robbery.... not someone sparking a joint in the privacy of their own homes.

My argument to the Government of Canada is, after reading the full 2002 Senate Report, that using Cannabis should not be a crime in the first place.

Shame on any politician who votes in favour of Bill C-15. My only hope is that if it does pass, the Canadian people will wake up and revolt by voting every single one of you out of Parliament.

(note: Bolding is mine)

No comments:

Post a Comment

High! Thanks for taking the time to leave a Comment. :)